Cambridge Bay Sees Food Bank Surge After Voucher Cut: When it comes to survival in the Canadian Arctic, food security is not just about what’s on the dinner table—it’s about survival, dignity, and cultural identity. In Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, families are sounding the alarm after the government cut the universal children’s food voucher program earlier this year. Since then, the local food bank has reported usage doubling, a painful reminder that food is more than fuel—it’s life, heritage, and future. This story isn’t just about Cambridge Bay. It’s about every family in Nunavut and across the Arctic where the cost of food often feels like it’s climbing higher than Mount Denali. With the voucher program shifting from universal support to case-by-case applications, many Inuit families are being left behind.

Cambridge Bay Sees Food Bank Surge After Voucher Cut

The story out of Cambridge Bay is a wake-up call. Families are struggling more than ever, not because they aren’t working hard, but because systems designed to support them have been pulled away. When a voucher cut doubles food bank use, that’s more than a statistic—it’s a call to action. Supporting Inuit communities means listening, acting, and respecting the right to food security. This is not charity; it is justice.

| Topic | Details | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Voucher program ended | $500/month per Inuit child under 18 and $250 for under 4 discontinued | Nunatsiaq News |

| Impact on families | Parents forced to cut essentials to buy food | Nunatsiaq News |

| Food bank demand | Cambridge Bay food bank usage doubled since voucher cut | Get The News Today |

| Policy shift | Universal support replaced by case-by-case applications under Inuit Child First Initiative | Government of Canada |

A History of Food Insecurity in Nunavut

Food insecurity in the Arctic isn’t new. For thousands of years, Inuit families thrived on country food—caribou, seal, arctic char, berries, and walrus. These foods weren’t just nutrition; they were the cornerstone of culture, tradition, and community connection.

Colonization disrupted this system:

- Inuit families were relocated to unfamiliar lands, often with fewer natural resources.

- Children were forced into residential schools, breaking the chain of knowledge around hunting and food preparation.

- Hunting was restricted by Canadian law, limiting access to traditional foods.

- Climate change has altered migration patterns, thinning ice and shortening hunting seasons.

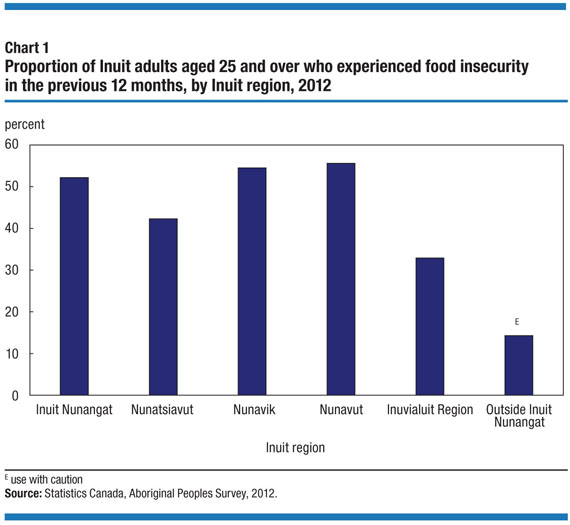

The result? A heavy dependence on imported, store-bought food—often unhealthy, always expensive. Today, Nunavut has the highest food insecurity rate in Canada at nearly 60% of Inuit households.

Understanding the Cambridge Bay Sees Food Bank Surge After Voucher Cut

The universal children’s food voucher program was created to help families shoulder the staggering cost of food. Each child under 18 received $500 a month, with an additional $250 for children under 4. This steady support was predictable, automatic, and made budgeting easier for families.

In March 2025, the program ended. Now, families must apply for support through the Inuit Child First Initiative (ICFI). This change creates barriers:

- Applications require paperwork many families find difficult to complete.

- Processing times leave families waiting weeks for approval.

- Not all families are approved, creating inequities between households.

This shift from universal to selective support means that many families who previously had a lifeline now find themselves scrambling.

Cambridge Bay: A Case Study in Struggle

Cambridge Bay, a community of about 1,800 people, is now facing a crisis. Since the voucher program’s cancellation, demand at the local food bank has doubled.

Volunteers describe shelves emptying in hours instead of days. Donations have not kept up, forcing tough decisions about rationing. Parents face heartbreaking choices: Do I pay rent, or do I buy groceries?

A Mother’s Story

Mary, a single mother of three, said:

“The voucher meant I could buy milk, fruit, and cereal without worrying about the rent. Now I’m back to skipping meals so my kids can eat. We’re struggling more than ever.”

This is not just Mary’s story. It’s the story of dozens of parents in Cambridge Bay and hundreds more across Nunavut.

Expert Voices

Community leaders and experts are sounding the alarm. Pamela Gross, Mayor of Cambridge Bay, has spoken about the immediate challenges families are facing. She emphasized that the removal of universal vouchers creates uncertainty in households already balancing on the edge of poverty.

Food policy experts add that food insecurity has a ripple effect. Families under pressure often resort to processed, calorie-dense foods that are cheaper but linked to long-term health problems like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Advocacy groups such as Food Secure Canada argue that red tape programs like ICFI do not adequately address the urgency of food insecurity in northern communities.

Why Food Prices Are Sky-High in Nunavut?

To understand why vouchers mattered so much, consider these realities:

- Shipping Costs – Most food must be flown in or shipped by boat during limited ice-free months.

- Harsh Climate – With no long growing season, large-scale farming is impossible.

- Limited Retail Options – Many communities rely on just one or two grocery stores, creating monopoly pricing.

- Infrastructure Gaps – Lack of roads connecting Nunavut to the rest of Canada means air freight is the default.

Examples of current food prices in Nunavut:

- 2 liters of milk: $14 to $16

- A watermelon: $55

- A bag of grapes: $28

These numbers highlight why every dollar of assistance matters.

Comparing Cambridge Bay to Other Communities

While Cambridge Bay has seen food bank use double, the situation is mirrored elsewhere:

- Pond Inlet: Families report skipping essentials like diapers to buy groceries.

- Rankin Inlet: Community freezers help but are not enough to meet rising demand.

- Iqaluit: High food costs remain, but greenhouse projects and hunter-supported food programs provide some relief.

Compared to the rest of Canada, where food insecurity averages 16% of households, Nunavut’s rate is nearly four times higher.

Practical Advice for Families

While policy change is critical, families are finding ways to cope:

1. Use Community Networks

Food banks, community kitchens, and traditional food sharing continue to be lifelines.

2. Apply Early for ICFI

Delays are common, so families are urged to apply before their situation becomes desperate.

3. Smarter Purchasing

Bulk-buying and cooperative shipping groups allow families to share costs. Nutrient-rich staples like oats, frozen vegetables, and powdered milk stretch further than snacks.

4. Advocacy

Collective action matters. Letters to government officials and petitions keep the issue visible in Ottawa.

Possible Solutions

Experts and community leaders have put forward several solutions:

- Reinstate Universal Vouchers: Provide predictable, equal support without red tape.

- Direct Subsidies on Healthy Foods: Ensure items like fruit, milk, and eggs are affordable.

- Invest in Local Food Systems: Hydroponic greenhouses, fisheries, and community gardens can reduce dependency.

- Universal Basic Income (UBI): Regular cash transfers that give families dignity and choice.

Internationally, countries like Greenland and Iceland have invested heavily in local food projects, reducing reliance on imports. These models could inspire Nunavut solutions.

How Readers Can Help?

Even if you live far from the Arctic, you can help:

- Donate to organizations supporting food security, such as Food First NL or Food Secure Canada.

- Share stories like Mary’s to raise awareness online.

- Support Inuit-owned businesses and advocacy campaigns.

- Contact policymakers and ask them to prioritize food security in northern Canada.

Small actions, when combined, create big ripples.

Voters in Opelousas Approve Sales Tax Renewal With a Twist

BBC Drops a Tax Secret That Could Save You Thousands in 2025

Trump Warns Tariffs on Nations ‘Discriminating’ Against US Tech — What It Means