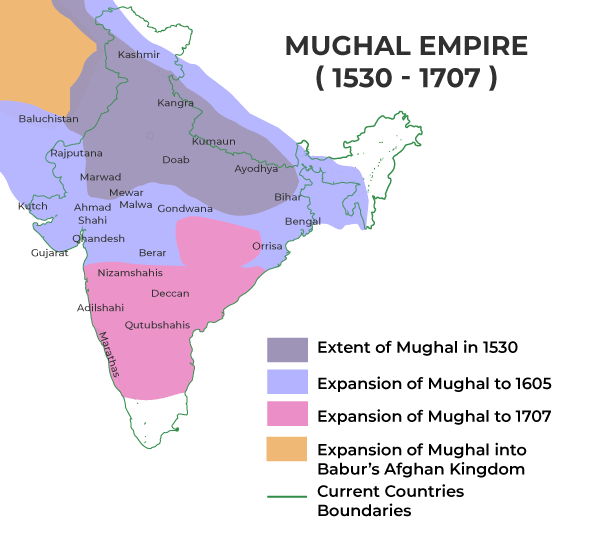

How the Mughals Collected Taxes: Ever wondered how folks got taxed in ancient India? Let’s take a trip down memory lane and talk about how the Mughals collected taxes. From your wheat field to the market road, if you lived under Mughal rule (roughly between the 1500s and 1700s), you paid the emperor his due. And trust us — he had it down to a science. Back in the day, taxes weren’t just a headache; they were the backbone of the empire. The Mughal taxation system was one of the most advanced of its time. And while the emperor was living large in his palace, common folks had to keep things rolling with grain, silver coins, and a whole lot of hustle.

How the Mughals Collected Taxes?

The Mughal tax system wasn’t just numbers on paper — it shaped the lives of millions. With land revenue at its core, backed by market, customs, and religious taxes, the empire built a system that was remarkably data-driven, but not always fair. While Akbar’s era focused on transparency and welfare, later rulers like Aurangzeb imposed policies that widened divisions. Its legacy continues to echo through the subcontinent’s fiscal structures. From measuring farmland to managing public roads and urban markets, the Mughals taught us that effective governance requires both organization and accountability — a lesson modern administrations would do well to remember.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Main Tax Type | Land Revenue (Zabt system) – ~33% of net crop yield |

| Key Tax Terms | Lagān, Zabt, Rahahdari, Katraparcha, Tamgha, Jizya, Zakat |

| Collection Method | Paid in grain or cash; assessed every 10 years using land surveys |

| Major Players | Zamindars, Mansabdars, Patwaris, Amal Guzars |

| Goods & Market Taxes | Transit tax, customs, market fees |

| Religious Taxes | Jizya (non-Muslims), Zakat (Muslims) |

| Judicial Oversight | Local courts, Faujdar’s office handled disputes |

| Reference | Wikipedia – Dahsala System |

How the Mughals Collected Taxes Explained

1. Land Revenue — The Big One

Let’s keep it simple. You grow crops? You owe the government a cut. This was known as the Zabt system, and it made up nearly 80% of the Mughal Empire’s total revenue.

How it worked:

- Every 10 years, officials took surveys of land and average crop yields.

- They divided land into types: Polaj (cultivated), Parauti (fallow), Chachar (temporarily fallow), and Banjar (barren).

- You paid roughly one-third of your net produce, either in grain or silver.

This system, designed by Raja Todar Mal under Emperor Akbar, was known as the Dahsala System, and it was considered a game-changer in fiscal governance. It provided long-term predictability for both farmers and the government. If the average yield over a decade in a district was 100 maunds per bigha, then one-third of that would be the expected tax — rain or shine.

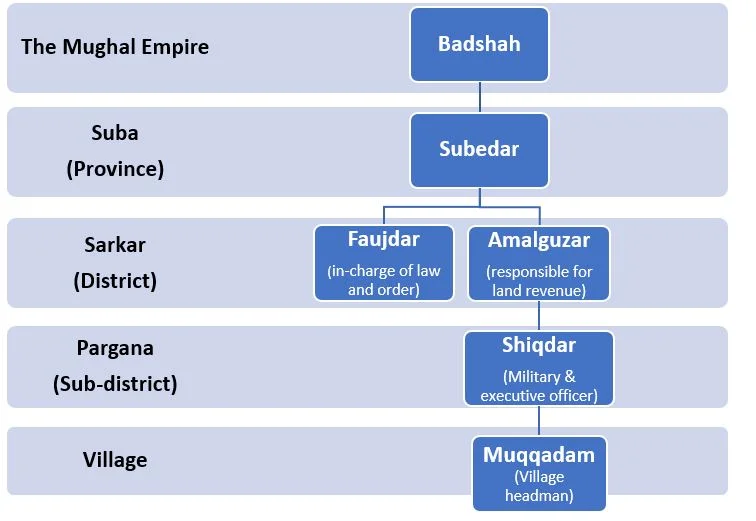

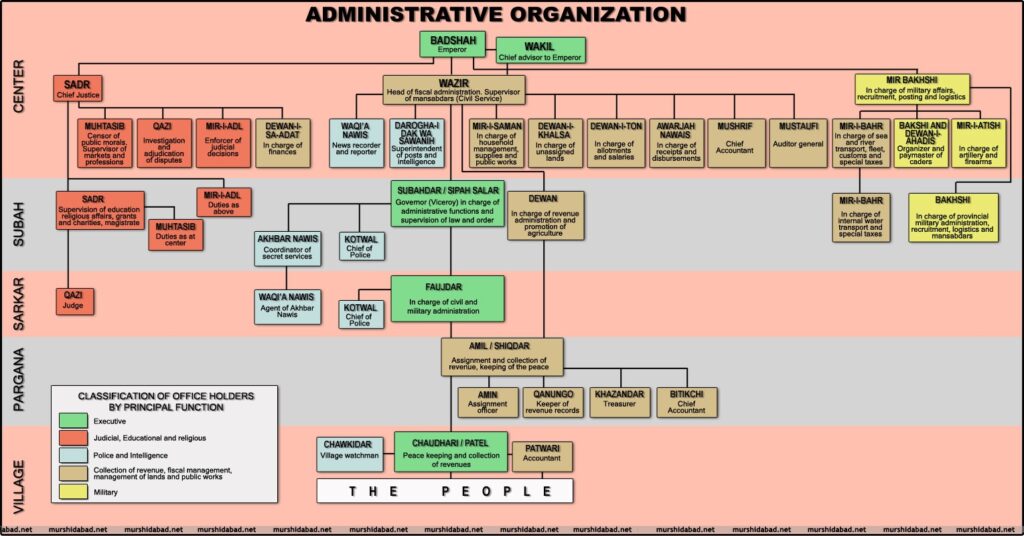

2. Who Collected Taxes?

Zamindars were local landholders who acted as intermediaries between the farmers and the Mughal state. They collected revenue, kept a commission (usually 10%), and were expected to maintain law and order. While some were benevolent, others became tyrannical and squeezed the peasants dry.

Mansabdars were ranked officers in the Mughal administration. Their salary wasn’t a fixed paycheck but a temporary assignment of land revenue — called jagir — from which they were expected to maintain troops for the emperor.

The emperor’s revenue staff also included:

- Patwaris: record keepers

- Amils: local revenue officers who calculated taxes

- Faujdars: military commanders with judicial powers in tax disputes

Taxes Beyond the Land

3. Transit Taxes — Rahadari

Moving goods meant paying Rahahdari, a tax levied on merchants transporting goods via carts, boats, camels, or bullocks. It was similar to today’s toll tax or customs checkpoint. The Mughals maintained a network of roads and rest stations called sarais, and Rahadari contributed to their upkeep.

This tax was levied at strategic locations such as state borders, river crossings, and entry gates to major cities like Agra, Lahore, and Delhi. Rates varied depending on the type and quantity of goods.

4. Market Taxes — Katraparcha

Merchants, artisans, and shopkeepers had to pay Katraparcha, a local market tax. This was calculated based on the value and type of goods being sold — spices, textiles, metals, etc. Local officials collected this to fund town maintenance, policing, and security services.

This tax helped the Mughals keep urban centers safe and markets regulated. In bustling cities like Surat or Delhi, katraparcha revenue was significant, especially from items like indigo, saltpeter, cotton textiles, and silk.

5. Customs Duty — Tamgha

International or interstate trade came under the purview of Tamgha, a customs or excise duty. Traders crossing into another province or importing/exporting from a port were taxed a certain percentage of their cargo’s value.

Muslim traders were often taxed at 2.5%, while non-Muslims were charged up to 5%, especially under conservative emperors like Aurangzeb. Ports like Surat, Cambay, and Thatta were hubs for this tax.

Religion-Based Taxes

6. Jizya and Zakat

One of the most debated aspects of Mughal taxation was religious tax policy.

Jizya was a poll tax imposed on non-Muslims, abolished by Akbar in a move towards secular governance, but reinstated by Aurangzeb in 1679. The tax was tiered:

- Wealthy: 48 dirhams

- Middle class: 24 dirhams

- Poor: 12 dirhams

The rationale was that non-Muslims didn’t serve in the military, so Jizya was a compensatory civic duty. But it alienated large sections of Hindu subjects and led to rebellions in places like Punjab and Maharashtra.

Zakat, meanwhile, was a religious alms tax (2.5%) paid by Muslims on their accumulated wealth. It was mostly used for social welfare and charity under Islamic law.

Mughal Money and Minting

The backbone of Mughal currency was the silver rupee, standardized during the reign of Sher Shah Suri and maintained by the Mughals. Coins were struck in silver, copper (called dam), and gold (mohur). Trade in urban areas was mostly cash-based, while villages continued to pay taxes in grain.

The empire maintained dozens of official mints, and coinage helped unify the vast territory under a single economic system — an impressive feat for a pre-modern state.

What If You Couldn’t Pay?

Life wasn’t easy. If a crop failed due to monsoon delays, locusts, or river flooding, and a peasant couldn’t pay taxes, there were three possible outcomes:

- Tax remission: The Mughal administration allowed for tax relief during natural calamities — but only if the local officer reported it.

- Deferment or loan: Some areas had village funds or state loans that were repayable next season.

- Confiscation or punishment: In corrupt or strict provinces, defaulters could lose their land, animals, or even be imprisoned.

In extreme cases, entire villages were abandoned during bad years — a situation the empire tried to avoid with balanced tax policies, especially under Akbar and Jahangir.

Law & Order: Tax Edition

The Mughal empire wasn’t all about swords and palaces — it had a functional bureaucracy and local justice systems. If you thought your tax was unfair or overcharged by a Zamindar, you could theoretically file a complaint with:

- The Faujdar (district military officer)

- The Qazi (Islamic judge)

- The Subahdar (provincial governor)

But justice wasn’t always swift or fair, especially if local officers were corrupt or in league with Zamindars.

Real-Life Example: Peasant Economics in 17th-Century Punjab

Imagine you were a small-scale wheat farmer producing 100 maunds (approx. 3700 kg) of wheat in a year. Here’s how your taxation might look:

- Land Tax (Zabt): 33 maunds

- Transit Tax (Rahahdari): 1 maund equivalent for transporting 10 maunds to the market

- Market Tax (Katraparcha): 2% of market value

- Religious Tax:

- Muslim: 2.5% Zakat on stored value

- Hindu under Aurangzeb: fixed Jizya amount (varied by class)

Net result: The family may retain only 50–60% of their annual produce for actual use or sale, making survival challenging during bad years.

The Economic Legacy of Mughal Taxation

- The British colonial system borrowed heavily from Mughal tax practices. The Permanent Settlement in Bengal was modeled on Zamindari structures.

- Today’s Indian revenue systems — including land measurement units, record-keeping offices, and market licensing — owe their roots to Mughal-era innovations.

- Mughal coins are still found in archaeological sites, showing the scale and reach of their financial network.

How Local Trade Helped July GST Collections Reach an Impressive Rs 1.96 Lakh Crore—The Inside Story