Tracking GST on Foreign OIDAR Services: In a world where we stream our favorite shows on Netflix, join webinars on Zoom, and store our files on Google Drive, it’s easy to forget that all these services come with tax implications—especially when they’re provided by foreign companies. But now, a new legal development in India has reignited the conversation around tracking GST on foreign OIDAR services. Recently, the Supreme Court of India chose not to directly intervene in this issue. Instead, it passed the baton to the GST Council, the body responsible for policy-making on Goods and Services Tax (GST). This decision holds weight for everyone—from everyday internet users to accountants, SaaS companies, and global tech giants. Let’s break it down in a way that makes sense for everyone—10-year-olds included.

Tracking GST on Foreign OIDAR Services

The Supreme Court’s hands-off approach is a call to action, not inaction. While courts interpret the law, tax enforcement belongs to policymakers. If foreign tech giants profit from Indian users, they must also contribute their fair share in taxes. As we move deeper into the digital age, India must ensure that foreign OIDAR services are held to the same standards as domestic providers. Anything less undermines our economy, our businesses, and our digital future.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| What Happened? | Supreme Court refused to enforce tracking; directed petitioner to file a representation with the GST Council |

| OIDAR Definition | Online Information and Database Access or Retrieval services like Netflix, Spotify, Zoom, Adobe, etc. |

| Legal Requirement | Foreign service providers must register under GST (Form REG-10) and file GSTR-5A |

| Current Loophole | No invoice-level tracking, no centralized database, poor audit trail |

| Risk | Loss of tax revenue, unfair competition for Indian service providers |

| Court’s Stance | Policy matter—only GST Council should decide |

| Visit Official Site | GST Council Official Website |

What Is OIDAR and Why It Matters in 2025

OIDAR stands for Online Information and Database Access or Retrieval services. It refers to any service delivered online by foreign companies directly to Indian consumers, with minimal or no human interaction.

Some everyday examples:

- Watching a movie on Netflix

- Attending a paid webinar on Zoom

- Subscribing to Canva Pro for design work

- Downloading an eBook from Amazon Kindle

- Using cloud storage via Dropbox

These services are provided over the internet by foreign entities, but are consumed in India. Under India’s IGST Act (Integrated GST Act), this counts as a supply of services in India, and should be taxed accordingly.

What Does the Law Say?

Per Section 13(12) of the IGST Act:

When OIDAR services are provided by a person located outside India and received by a non-taxable online recipient in India, the supplier is liable to pay IGST.

This means that even if just one individual in India—say, a teenager watching Netflix—consumes a service, Netflix must pay GST to the Indian government.

And how should that be done?

- Register for GST using Form REG-10

- File monthly returns via GSTR-5A

- Pay the applicable 18% IGST

But here’s the catch: compliance is voluntary. And without any strong enforcement mechanism, many foreign providers skip the process altogether.

What the Supreme Court Said: Let the Council Decide

In a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed in 2025, a petitioner argued that the Indian government lacks a mechanism to:

- Track the actual revenue earned by foreign OIDAR providers

- Verify if GSTR-5A is being filed correctly

- Ensure that GST is paid on all such services

The petitioner asked the Court to order the tax authorities to strengthen enforcement.

But the Supreme Court, led by Justices B.V. Nagarathna and K.V. Viswanathan, took a different route:

“The GST Council is the proper authority to examine and decide on such policy issues. The petitioner is free to file a representation with the Council.”

So instead of issuing a binding legal directive, the Court deferred the responsibility to the GST Council.

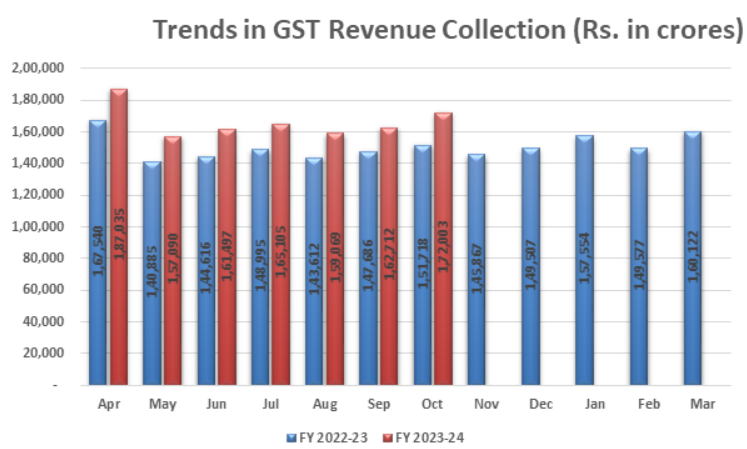

The Revenue Leakage Problem

Let’s not sugarcoat it—this is a massive hole in India’s tax bucket. Here’s why:

- No Invoice-Level Reporting

- GSTR-5A doesn’t require itemized invoices.

- There’s no detail on which Indian customer bought what.

- No Audit Trail

- Indian tax authorities can’t audit foreign companies.

- There’s no way to confirm reported revenue.

- No Penalty Enforcement

- Many foreign firms ignore the rules without facing consequences.

According to a report by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India, lax enforcement could result in ₹3,000–₹5,000 crore ($360M–$600M) in lost GST revenue annually.

Meanwhile, Indian service providers offering similar products are held to strict rules and high compliance costs.

How Do Other Countries Handle It?

India is not alone in taxing foreign digital services. Here’s how others do it:

| Country | Digital Services Tax Strategy |

|---|---|

| European Union | VAT under the Mini One Stop Shop (MOSS) system |

| Australia | “Netflix Tax” – 10% GST collected via mandatory foreign registration |

| Indonesia | 10% VAT on digital services since 2020 |

| United Kingdom | 2% Digital Services Tax on large foreign tech firms |

| South Korea | Foreign companies must file VAT via electronic reporting system |

These countries have tech-enabled tracking systems, better audit mechanisms, and penalties that actually bite.

India? We’ve got the laws… but not the teeth.

Real-World Example: What’s at Stake

Let’s say a graphic designer in India uses Adobe Creative Cloud, a foreign OIDAR provider. Adobe makes money from that Indian customer. If Adobe doesn’t register for GST and skips filing GSTR-5A, the Indian government loses tax and Indian SaaS providers get undercut.

Multiply that by thousands of users and dozens of platforms, and we’re looking at a serious dent in national revenue.

A 5-Step Roadmap for the GST Council

If the GST Council wants to take this issue seriously, here’s what it needs to do:

1. Revamp GSTR-5A

Add mandatory invoice-level reporting and link it with PAN numbers or email IDs of Indian customers.

2. Build a Centralized OIDAR Registry

List all foreign service providers operating in India. Make compliance status public and searchable.

3. Mandate Registration Beyond Threshold

Set a minimum revenue threshold (e.g., ₹20 lakh) beyond which foreign players must register and comply.

4. Use Fintech & Payment Data

Track credit card payments made to foreign entities using real-time payment systems like UPI, Visa, and Mastercard.

5. Launch a Global Compliance Drive

Partner with other countries under BEPS 2.0, OECD tax treaties, and push data-sharing agreements.

Expert Views on the Matter

CA Meenakshi Narula, a GST advisor in Mumbai, notes:

“India’s digital economy is expanding fast, but our tax system hasn’t caught up with the pace. Unless the GST Council creates an audit mechanism, we’ll keep losing revenue and domestic firms will keep bleeding.”

Similarly, a 2024 white paper by NIPFP (National Institute of Public Finance and Policy) emphasized:

- The need for digital enforcement tools

- Tighter compliance monitoring

- Real-time analytics using fintech data

Gauhati HC Rules GST SCN Invalid Without Personal Hearing Date

GST Council Considers Amnesty That Could Save Small Businesses Lakhs in Penalties

GST Cracks Down on Fake Firms — 11 Bogus Companies Served Notices Amid Ongoing Probe

What’s Next? All Eyes on the GST Council

The onus is now on the GST Council to take action:

- Will they reform GSTR-5A?

- Will they build a real-time tracking system?

- Will they enforce penalties?

With India’s digital economy projected to hit $1 trillion by 2030, even a 1% compliance improvement could lead to thousands of crores in revenue.